St Croix River Road Ramblings

Welcome to River Road Ramblings.

Online Free Local History Books by the Rambler

Books for Sale at Amazon by the Rambler

Tuesday, January 26, 2016

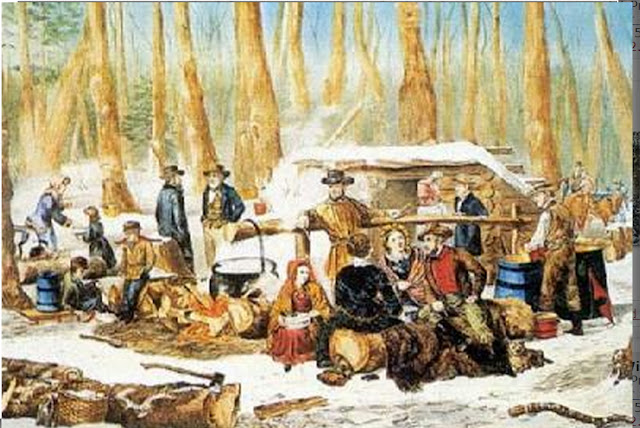

MAKING MAPLE SUGAR By Charles Duddley Warner

I THINK there is no part of farming which the boys enjoy more than the making of maple sugar. It is better than blackberrying, and nearly as good as fishing; and one reason why he likes this work is, that somebody else does the most of it. It is a sort of work in which he can appear to be very active, and yet not do much.

In my day, maple sugar making used to be something between picnicking and being shipwrecked on a fertile island, where one should save from the wreck tubs, and augers, and great kettles, and hen's eggs, and rye-and Indian bread, and begin at once to lead the sweetest life in the world.

I am told that it is something different nowadays, and that there is now more desire to save the sap, and make good, pure sugar, and sell it for a large price, than there used to be; and that the whole fun and poetry of the business are pretty much gone.

I remember the New England boy (and I am very intimate with one) he used to be on the watch in the spring for the sap to come. Perhaps he knew it by a feeling of something starting in his own veins, — a sort of a spring stir in his legs and arms, which tempted him to stand on his head, or throw a handspring, if he could find a spot of ground from which the snow had melted.

Perhaps the boy has been out digging into the maple trees with his jackknife; at any rate, he comes into the house in a good state of excitement — as if he had heard a hen cackle in the barn — with, "Sap's runnin'!"

Then indeed the stir and excitement begin. The sap buckets, which have been stored in the garret over the woodhouse, are brought down and set out on the south side of the house, and scalded. The boy is everywhere present, superintending everything, asking questions, and filled with a desire to help on the excitement.

It is a great day when the sled is loaded with buckets, and the procession starts for the woods. The sun shines almost unobstructedly into the forest, for there are only naked branches to bar it; the snow is beginning to sink down, leaving the young bushes spindling up everywhere; the snowbirds are twittering about, and the noise of shouting, and the blows of the ax, echo far and wide.

In the first place, the men go about and tap the trees, drive in the spouts, and put the buckets under. The boys watches all this with the greatest interest. He wishes that, sometimes, when a hole is bored in a tree, the sap would spout out in a stream, as it does when a cider barrel is tapped, but it never does: it only drops, sometimes almost in a stream, but, on the whole, slowly, and the boy learns that the sweet things of the world do not come otherwise than drop by drop.

Then the camp is to be cleared of snow. The shanty is re-covered with boughs. In front of it two enormous logs are rolled nearly together, and a fire is built between them. Upright posts with 90

crotches at the top are set, one at each end, and a long pole is laid on them; and on this are hung the great caldron kettles.

The huge hogsheads are turned right side up and cleaned out, to receive the sap that is gathered. And now if there is a good "sap run," the establishment is under full headway.

The great fire that is kindled in the sugar camp is not allowed to go out, night or day, so long as the sugar season lasts. Somebody is always cutting wood to feed it; somebody is busy most of the time gathering in the sap; somebody is required to fill the kettles and see that the sap does not boil over.

It is not the boy, however; he is too busy with things in general to be of any use in details. He has his own little sap-yoke and small pails, with which he gathers the sweet liquid. He has a little boiling place of his own, with small logs and a tiny kettle.

In the great kettles the boiling goes on slowly, and the liquid, as it thickens, is dipped from one to the other, until in the end kettle it is reduced to syrup, and is taken out to cool and settle, until enough is made to "sugar off."

To "sugar off" is to boil the syrup till it is thick enough to crystallize into sugar. This is the grand event, and is only done once in two or three days. But the boy's desire is to "sugar off" perpetually. He boils his syrup down as rapidly as possible; he is not particular about chips, scum, or ashes; he is apt to burn his sugar; but if he can get enough to make a little wax on the snow, or to scrape from the bottom of the kettle, with his wooden paddle, he is happy. A great deal is wasted on his hands and the outside of his

face and his clothes, but he does not care —he is not stingy.

To watch the operations of the big fire gives him constant pleasure. Sometimes he is left to watch the boiling kettles. He has a piece of pork tied on the end of a stick, which he dips into the boiling mass, when it threatens to go over.

He is constantly tasting the sap to see if it is not almost syrup. He has a long round stick, whittled smooth at the end, which he uses for this purpose, at the constant risk of burning his tongue. The smoke blows in his face; he is grimy with ashes; he is altogether such a mass of dirt, stickiness, and sweetness that his own mother wouldn't know him. He likes, with the hired man, to boil eggs in the hot syrup; he likes to roast potatoes in the ashes; and he would live in the camp day and night if he were permitted.

Some of the hired men sleep in the shanty and keep the fire blazing all night. To sleep there with them, and awake in the night and hear the wind in the trees, and see the sparks fly up in the sky, is a perfect realization of all the adventures he has ever read. He tells the other boy, 91 afterward, that he heard something in the night that sounded very much like a bear. The hired man says that he was very much scared by the hooting of an owl.

The great occasions for the boy, though, are the times of the "sugaring off." Sometimes this used to be done in the evening and it was made the excuse for a frolic in the camp. The neighbors were invited, and sometimes even the pretty girls from the village, who filled all the woods with their sweet voices and merry laughter and little affectations of fright.

At these sugar parties, every one was expected to eat as much sugar as possible; and those who are practiced in it can eat a great deal. It is a peculiarity about eating warm maple sugar, that, though you eat so much of it one day as to be sick and loathe the thought of it, you will want it the next day more than ever.

At the "sugaring off" they used to pour the hot sugar upon the snow, where it congealed into a sort of wax, without crystallizing; which, I do suppose, is the most delicious substance that was

ever invented; but it takes a great while to eat it. If one should close his teeth firmly on a ball of it, he would be unable to open his mouth until it was dissolved. The sensation, while it is melting, is very pleasant, but one cannot talk.

The boy used to make a big lump of this sugar wax and give it to the dog, who seized it with great avidity and closed his jaws on it, as dogs will do on anything. It was funny, the next moment, to see the expression of surprise on the dog's face, when he found he could not open his jaws. He shook his head; he sat down in despair; he ran round in a circle; he dashed into the woods and back again. He did everything except climb a tree and howl. It would have been

such a relief to him if he could have howled, but that was the one thing he could not do.

Like this story? Charles Dudley Warner was born in 1829 and wrote about "Being a Boy" in 1877 looking back to his own childhood. Try the whole book for free at

https://books.google.com/books?id=B5PnCaGqAa4C